A brief intro to Beautiful game mechanics: I find games incredibly interesting. They are the only form of entertainment that we do not experience passively but actively engage with. We are just now starting to explore and understand what we can do with games, and while a lot of games still seem to fulfill power fantasies more than anything else, we are seeing more and more creators from all over the world mess around with games to not only tell their stories but to also to share their worldview and allow us to experience it. One way to study games is to break them down to their smallest components, the mechanics, to understand what they are made of and what are the effect they are trying to obtain on us. A game mechanic can be as beautiful and meaningful as a brush stroke in a painting, as an editing technique in cinema, as a writing style in literature. Let’s see if I can convince you. I’ll try to write a few Beautiful game mechanics posts and in each one I’ll dissect a particularly interesting mechanic. I’m not necessarily a game designer myself, but I have a toy microscope and I’m not afraid to use it. With that out of the way, let’s dive in.

⁂

Apocalypse World by Vincent Baker is a 2010 role playing game that created a genre with its clever approach to storytelling and design. Dozens of games today use the Powered by the Apocalypse (PbtA for short) set of rules Apocalypse World is also based on. The way it handles player dice rolls is incredibly interesting and one of my favorite game mechanics in general.

When cool things happen in a Powered by the Apocalypse game, they happen because someone triggered a move. This means that they said that their character was going to do something not mundane that requires taking some risks. All moves follow the same general approach in Powered by the Apocalypse games: you roll two six sided dice, you add optional bonuses coming from your character sheet and read the result. If the result is above 10, you succeed without compromises: you do what you wanted to do. If the result is between 7 and 9, you still succeed but the game master will add a complication, a hard bargain or a choice that your character will have to face no matter what. If the result is below 6, you fail and the game master tells you what happens… you won’t like it.

There are several smaller variations on this generic approach but in general every move in Powered by the Apocalypse games follows this principle. There are two aspects of this that I find beautiful, tightly connected.

The first aspect is that this mechanic blends rules and narration. Every result pushes the story forward in a «snowballing effect». Every move has consequences that push the narration and require other moves. In many classic role playing games often things either happen or don’t. You want to stab that dragon? It’s either: you roll, you fail and you miss or you roll, you succeed and you hit. In Powered by the Apocalypse games you can still miss or hit, but you also have a beautiful middle ground. You roll, you get a success with a compromise: your sword cuts through the dragon scales (success) but… it’s also stuck there and it doesn’t want to come out. You don’t have another weapon and the dragon slowly turns toward you (consequences). And then the game master gets to ask you the most beautiful question ever: «what do you do?», snowballing the failure into another action either by you or your friends.

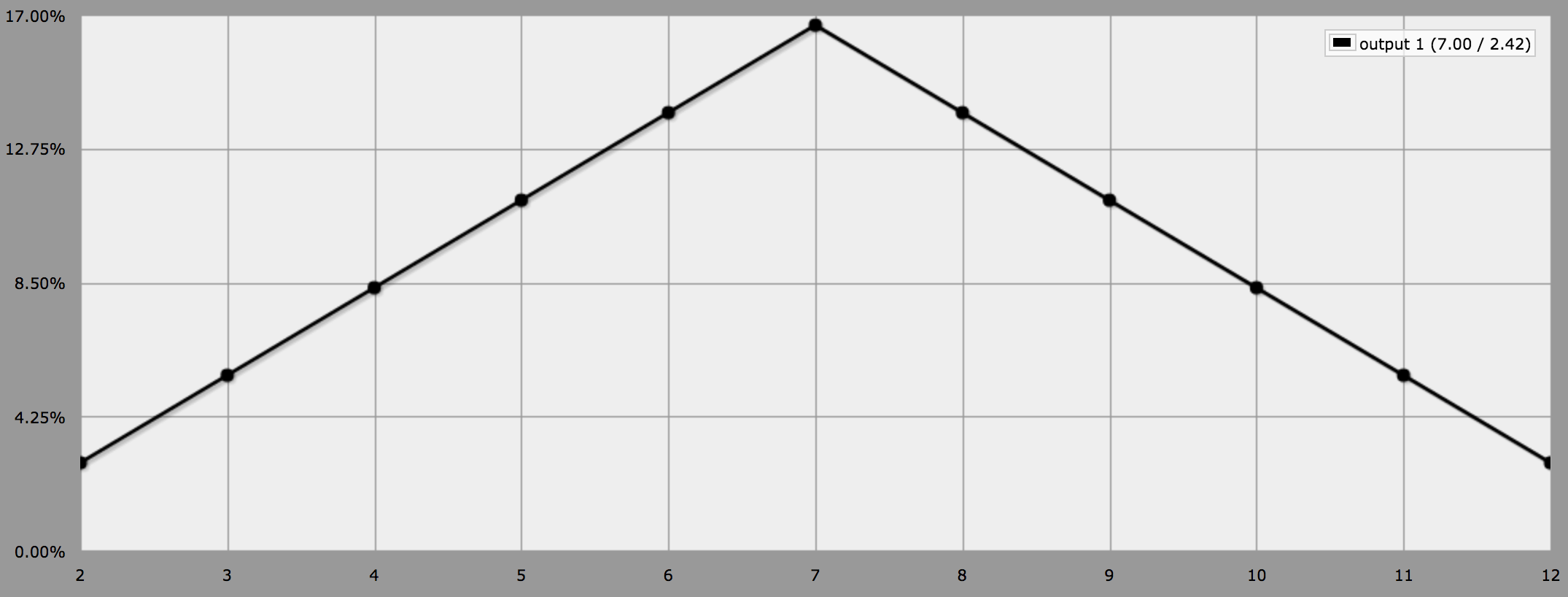

The second aspect I love is exquisitely mechanical and enhances the beauty of that middle ground. If you look at the chart below you’ll notice two things: first of all that any player roll (even without optional bonuses) has slightly more than 50% chances of succeeding. And, second, that the probabilities tend to land in the 7 to 9 bracket. Meaning that there’s a higher chance that a roll will result in a success with consequence (making things interesting, pushing the action forward!).

Many role playing games assign actions to a single die roll (in classic D&D you roll a twenty sided dice plus bonuses, in example). Adding a second die allows for a more interesting range of results, because they create an average result and a less common low or high result. So true successes and failures are more meaningful, and common results actually constantly push the narration forward.

Leave a Reply